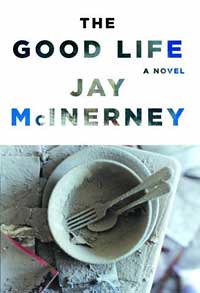

(image via gothamist)

The Corsair has just finished reading Jay McInerney's bittersweet take on Eros and Death in Woody Allen's post-9/11 --and pre-"Match Point" -- New York. Granted, the namedropping in a McInerney novel is cloying -- it actually interrupts his sparkling flow of narrative on more than one occasion -- but the work itself is pretty damned impressive.

Luke McGavok is a macher, an ex-Master of the Universe, an investment banker-type who drops out of the Game to, in no particular order, write the definitive book on Japanese samaurai film (Is it now obligatory for every American writer of a certain age have to include a shout-out to Toshiro Mifume?), spend time with his troubled daughter Amber, and, perhaps, save his crumbling marriage to an icy, beautiful socialite named Sasha, who is, at the end of the first chapter, cuckolding him publicly on the dance floor with a Ron Perlmanesque still-in-the-game billionaire player. (Averted Gaze)

Then comes September 11. Roughly one-third into the narrative, the stench of the death surrounding the fallen Twin Towers permeates the rest of the book, contaminating the bittersweet Eros of Luke's first meeting with Corrine Calloway -- his Platonic Half -- through the toxic haze and airborne ash of the terrorist attack on ghostlike Lower Manhattan on that fateful day.

The acrid scent of decomposing bodies, boiling chemicals, congealed lunchmeats and still-burning metal wafts through the impromptu soup kitchen where Luke and Corrine slowly fall in love, amidst the loss (and, in artful counterpoint, some colorful characters), providing nutriment for the rescue workers at the gaping hole that used to be the World Trade Center.

Does Jay McInerney exploit September 11th as a compelling narrative device?

We think not, althogh the case has been made -- exhaustively. The reviews have, quite frankly, been brutal. The various negative reviewers are singular in their attack on McInerney's excessive namedropping-cum-unpaid product placements, which, we'll agree, is quite indefensible and often tasteless. Worse than that, literarywise, McInerney stops the plot at critical moments with his inclusion of some status-enhancing but plot-deadening product.

But the story, the characters, and the writing is unassailable. The development of the compicated inner life of Corrine is particularly impressive, maybe the best personality construction that McInerney has ever ventured to put on paper. "Cor" is Latin for heart; Corrine is, essentially, the heart of this story. Corrine is the wife of an asshole publishing industry mini-mogul who cheats -- incessantly -- with young, acid-tongued quasi-intellectual underlings (he is the Upper West Side counterpart of Luke's Upper East Side Sasha).

After being confronted -- brutally -- by one of her husband's publishing industry biscuits at a highbrow dinner affair on the Upper West Side (One doesn't quite know what is more mortifying in the authors mind: The actual betrayal, or the embarrasment at its revelation in front of the assemblage of sophisticated intellectuals), Corrine distances herself from that world. Enter: Luke.

The Upper West Side fades. As Luke and Corrine's relationship develops, their marriages, predictably collapse. Amber, unskillfully navigating an ocean of Manhattan Private School "Mean Girls," attempts to kill herself, is rescued, then escapes her high-priced clinic to go down South to her Grandmother's. As Luke ventures back to the protective cocoon of his family, he finds, somewhat, what he lost in mindlessly pursuing the rat-race of the city (which, he learns, is a misbegotten Freudian attempt to match the social distinctions of his mother's lover). In the process he reconnects with both his Mother, from whom he was estranged, and his daughter, who, it seems, was only fucked-up by association with Manhattan private schools.

We won't spoil the ending. We'll only say that it is bittersweet, and that it ends, in late autumn, amid the fallen leaves, at the New York City Ballet's seasonal Nutcracker (after a chilly November bout of Eros in the West Village, not far from Ray's Pizza).

Are we doomed to our social roles we presently inhabit no matter how hard we try to escape, no matter how vacuous they become in the lengthening shadows of the terrorist attack of September 11? That seems to be the question McInerney is asking through the soot and Death and Eros that emanate from the pages of this well-executed mini classic.

No comments:

Post a Comment